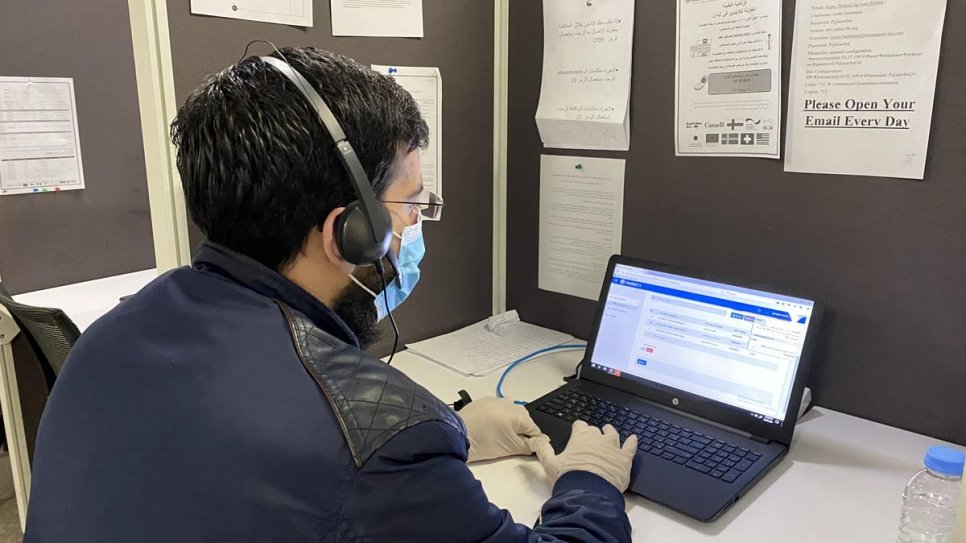

A Lebanese telephone operator wearing protective equipment answers refugees’ calls. © UNHCR

With most face-to-face humanitarian programmes now on hold, region’s largest call centre offers vital support to struggling refugees during COVID-19 lockdown.

By Rima Cherri in Jal El Dib, Lebanon

In a large, open-plan office on the outskirts of the Lebanese capital, Beirut, telephone operators wearing headsets over blue surgical face masks sit separated from their colleagues by several empty cubicles. A country-wide lockdown is in place to slow the COVID-19 outbreak, but workers here are still fielding hundreds of calls each day.

These key workers are keeping the lines open at the region’s largest and busiest call centre for refugees. Run jointly by UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and the World Food Programme, it provides increasingly vital assistance now that a number of face-to-face humanitarian activities must be carried out remotely to combat the virus.

“We received the first COVID-19-related call on 2 March, but since then … the number is increasing every day,” said Jerome Seregni, a UNHCR Communication with Communities Officer who oversees the centre. UNHCR has strengthened capacity at the call centre to ensure it can respond to increased demand from refugees at a time of growing anxiety.

“The call centre has a critical role now, because regular outreach activities have been limited by the restrictions on movement to fight the virus, but people still have access to phones and social media,” he added.

Established in 2015, the centre receives almost a million enquiries per year from refugees about protection services and assistance, with around 60 per cent of the country’s refugees having used the service.

“The call centre has a critical role now.”

With some 910,000 registered Syrian refugees, plus more than 200,000 Palestinians, it hosts more refugees per capita than any other country. Even before the pandemic emerged, a worsening economic crisis was already putting more pressure on vulnerable Lebanese and refugee communities.

Since mid-March, all of the country’s inhabitants – including refugees – have had to strictly limit their movement to limit the risk of infection. As a result, UNHCR has had to temporarily suspend activities at its network of reception and community centres throughout the country due to the gatherings they prompted and the necessity to respect physical distancing as a preventive measure.

Alternative mechanisms have been introduced to maintain humanitarian operations, including strengthening remote assistance mechanisms such as the call centre.

Priority is being given to the COVID-19 response, with measures including distributions of soap and other sanitation materials to refugees, construction of isolation areas in or near informal refugee settlements, and cooperation with partners and the authorities to expand the capacity of Lebanon’s health system for those requiring hospitalization or intensive care.

While there have so far been no confirmed cases of the virus among refugees in Lebanon, Seregni says the centre is fielding an increasing number of calls from refugees seeking advice about prevention or help dealing with the financial impact of the restrictions on movement.

“Most of the calls are about health, food, cash, sanitizers, soap and other assistance that has been affected by the crisis, especially for refugees who cannot travel around and do the work they used to do before the restrictions,” he explained.

Seregni recounted several recent calls to the centre from refugees unable to work because of the crisis who said they could no longer afford to buy enough food to feed their families.

With the current restrictions on movement compounding the country’s economic crisis, the dire situation faced by many refugees was confirmed by Jamal Zhaim, one of around 20 Lebanese telephone operators still working at the centre, with special authorization, during the crisis.

“Refugees say they are unable to provide a living for their families because of the restrictions,” he said. “This is a very serious message.”

“I feel like I am helping people.”

In response, Zhaim offers callers details of the types of assistance available, directs them to more expert information and advice, and shares official guidance on how to protect themselves from infection. He also refers cases that require specialized assistance such as protection and mental health support for follow-up by UNHCR and its partners.

Asked whether he had any reservations about continuing to go to work while many in the country were staying at home for their own protection, Zhaim said he had confidence in the new health protocols put in place and was glad to be able to play a role in the COVID-19 response.

“I still go to the centre because it has taken measures to protect us from the virus, such as social distancing, masks, gloves and hygiene kits. I come alone and in my own car,” he said.

“I feel like I am helping people to reach the services they need and take the necessary measures to protect themselves from the virus, and also protect people around them and the community,” Zhaim added.

“This is our role, and I feel I have a duty to deliver the refugees’ queries in this time to those who can help.”

Originally published by UNHCR on 16 April 2020