Child refugee Zoera, in faded red dress with green headscarf, attends class at Djabal camp in Chad. © UNHCR / S.Cherkaoui

DJABAL REFUGEE CAMP, Chad, Dec 14 (UNHCR)—Anas, 10, and Zoera, eight, leap out from under their mosquito net into the cool morning air. It is only 6:45 when brother and sister rush through the sandy lanes of the labyrinthine Djabal refugee camp in eastern Chad.

“Quick, quick, we need to get to school!” Zoera urges Anas with excitement. Both are Sudanese children born in exile in Chad.

When war broke out in Darfur in 2003, their parents were forced to flee their home to escape the violence there that has claimed more than 480,000 lives and displaced 2.4 million people.

While the crisis and its dire humanitarian consequences have all but faded from international headlines, Chad continues to host 120,000 Sudanese refugee children of school age. They have not been forgotten by the Government of Chad or the UN Refugee Agency.

An important change began in 2014, when the Ministry of Education decided to include refugees into the national school curriculum as a means to foster their integration, improve the quality of education and help them make the most of future opportunities.

As soon as Anas and Zoera reach the school playground, they line up with the other children and join in singing Chad’s national anthem in a cheerful cacophony. When the song ends, the children rush to the classrooms, where they receive instruction in Arabic—one of Chad’s two official languages, along with French.

There is a shortage of desks, and Anas and his 30 classmates unroll mats on the floor. As in most classes, only the teacher has a text book, although UNHCR is working to provide a text book for every child in the near future.

Once the teacher enters the classroom it is time for a reading lesson in Arabic. Pupils, aged six to 10 promptly raise their hands to answer the teacher’s questions. Meanwhile, in her classroom, Zoera studies maths, and is busy solving an equation.

The long-term strategy of integrating refugees into the national curriculum – which includes training Sudanese refugees as teachers—is seen as essential to sustainability, coming after many families have spent 10 years or more in exile, with chances of returning to Sudan still appearing slim. UNHCR’s partnership with the Educate A Child Programme (EAC) of the Education Above All Foundation—which was today renewed for three years—is key to tackling the challenges linked to this critical transition.

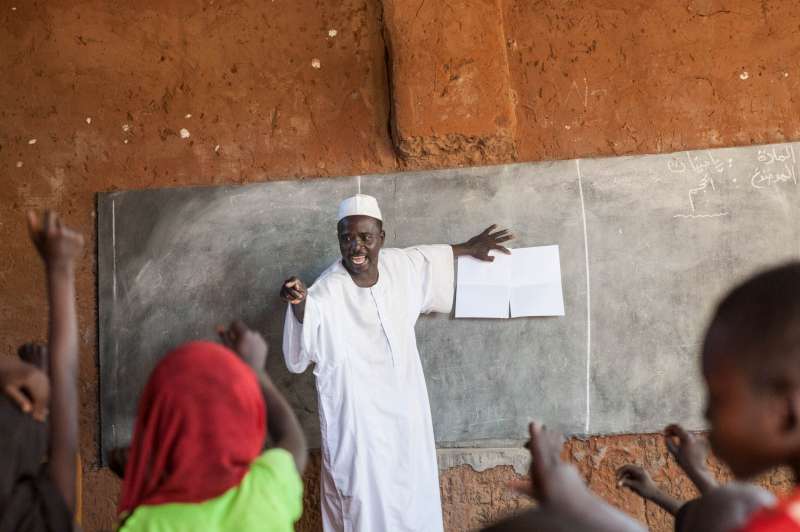

Sudanese refugee and schoolteacher Ibrahim Issakh Khamiss teaches a class at Djabal camp in Chad. © UNHCR / S.Cherkaoui

So far, the programme has helped over 1,700 unqualified refugee teachers to attend training and adapt to Chad’s curriculum. A further 167 refugee teachers were provided with a condensed course and obtained the appropriate diplomas.

Ibrahim Issakh Khamiss, 46, is one of them. “After the training I received, my teaching has become more fun, livelier and, as a result, my pupils pay more attention,” he said. There is little question that Ibrahim’s class is the most enthusiastic. His students’ voices resonate in the courtyard with cries of “Ustad, Ustad!—Teacher, Teacher!”

The heat is at its peak when the bell rings. The students pack up their mats and rush home. Anas and Zoera feast on a plate of beans. They both know how lucky they are to have parents who send them to school. “Many of our friends do not study, they work in the fields with their families,” Anas laments. But other school comrades and their families do benefit from specific programmes.

UNHCR has supported vulnerable households with micro-loans so that families are able to cover the costs of sending their children to school. This allows families to start small businesses, improve their living standards and let the children go to school.

So far, over 13,000 children were enrolled with the support of the EAC programme. And a further 30,000 out-of-school children are expected to be enrolled over the next three years, including supporting over 22,000 out-of-school children with education grants.

While Sudanese refugees are taught Arabic, they still need to learn French as a second language. To that end, 256 Chadian teachers have been deployed in the camps to teach French. Zoera and Anas are not learning French yet, but that’s not enough to discourage them. At nightfall they meet with a French-speaking refugee and ask him jokingly: “Comment ça va, Monsieur?” “You see!” Anas said. “In no time we’ll be able to speak like a Chadian!”

The first results of this curricular transition are already visible. At the exams ending middle and high school, refugee students have fared well above the national average, thus giving hope to many students of eventually entering Chadian universities. Ibrahim is proud of this achievement.

“Ignorance led to the war in Darfur,” he muses. “It is against this ignorance that we are fighting. Children need education for, when we return to Darfur, it will be the only guarantee of peace.”

You can learn more about the Education Above All Foundation here.