Tired refugees fleeing war in Syria and elsewhere at the Croatian government transit centre in Opatovac near border with Serbia. © UNHCR / I. Pavicevic

OPATOVAC, Croatia, Sept 22 (UNHCR) — In their thousands they streamed across a disused, now re-opened Croatian border post at Bapcek: Afghans, Syrians, Iraqis fleeing war in the Middle East into a country where the memories of its own conflict in the early-90s are still raw and vivid.

For hours, they walked along a road peppered by pock-marked churches and ruined buildings, memorials to a time when Croatians too were refugees. And all along the way, people who remembered all too well the bitter sting of displacement gathered to offer them tea, bread, grapes and some words of kindness.

Katerina Jurina, 82, clad in a black scarf and spotted dress, quietly wept as she recalled her ordeal, not so long ago in a long lifetime, when she was packed in a train for two weeks before being sent to safety on the coast. “I could cry,” she said. “I remember the hard times. We went by train, but they are walking. So many little kids. God help us.”

“We were all refugees during the war,” said Anton Papac, who laid out grapes on a bench, and called over the exhausted and the anxious for a brief moment’s rest. “Empathy is normal. So many kids… Syria is so far away.”

The refugees came drawn by promises of safety, a chance to start again and raise their children away from the bombs and the bullets. But their journey has been long and harrowing, filled with dangers of its own.

“We passed through villages in Iran with big dogs, which attacked my wife and child. And the boat was very dangerous,” said Amin Karimi, a 32 year old from Afghanistan, carrying his six- month-old son, Ahmad, in a sling. “I am very happy I arrived here.”

At the Croatian transit centre in Opatovac, their ordeal was not yet over. Hundreds pushed against fences outside the front gates, awaiting their turn for a painfully slow registration process. Inside, the relative calm of yesterday was beginning to fray, as the camp grew more congested.

On Monday night, 1,500 people were allowed to continue their journey, but the flow came to a halt during the day, and people were growing increasingly afraid that they would have to stay. The ground near the centre gates was boggy with mud as crowds pressed forward in hopes of any news, and the shadiest spots under the pine trees were crammed tight with men, women and children trying to sleep off the stress.

“We are afraid they will keep us here,” said wheelchair bound Gomana Ghonime, a mother of two, outside a child-friendly play area. She added: “It was very cold last night. We only had two blankets for the four of us.”

UNHCR staff spent the day helping to reunite families who have been separated, identify the most vulnerable to provide them with support and to pass information. The Croatian Red Cross said food distributions were becoming more difficult—and now had to be supported by the police. While the situation remained under control, there was a clear sense of mounting pressure throughout the day.

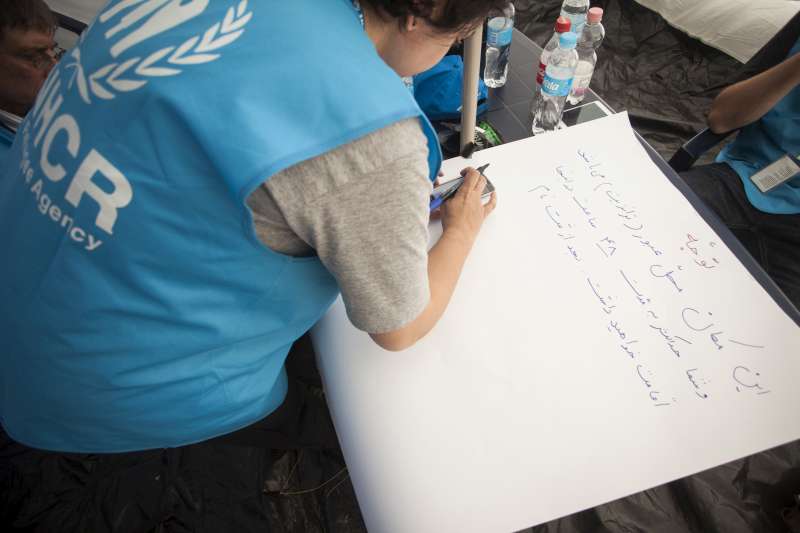

Mandana Amiri, UNHCR protection officer, writes an information poster in Farsi for refugees at the Croatian government transit center in Opatovac, near the Serbian border. © UNHCR / I. Pavicevic

Nonetheless, Barbara, a 24-year-old physiotherapist from the nearby town of Osijek, who volunteers her spare time with the Red Cross, had no doubts she was doing the right thing. “I am a war child,” she said. “Back then my mother was with me for two months in Austria. I just feel I must help them.”