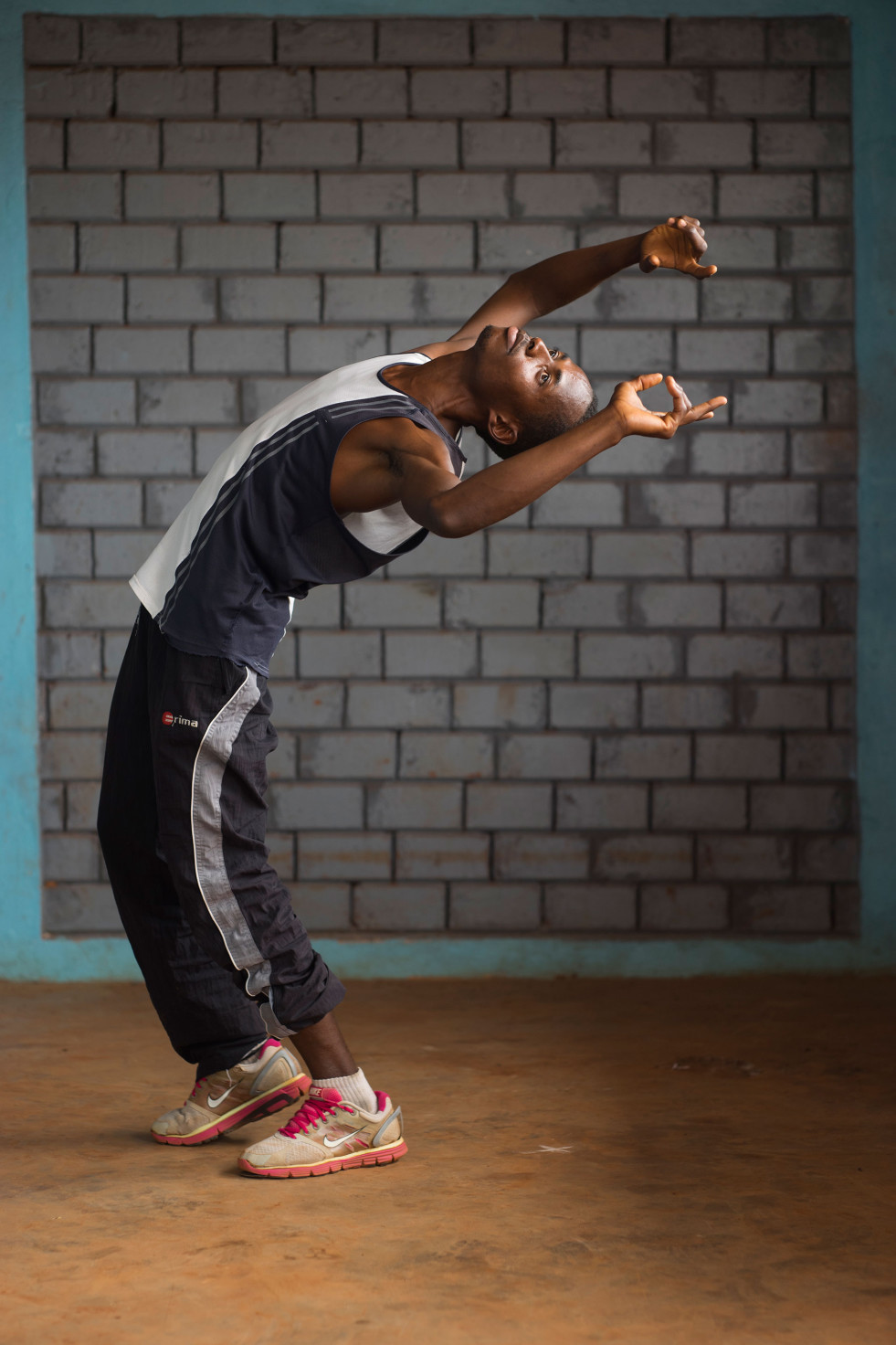

William Kopati, 22, won a national championship in high-jumper. © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

They were at the top of their game when fighting shook the Central African Republic. Now living as refugees, six stars wonder if they’ll ever compete at that level again.

Martial was a national champion in karate. William won medals as a high-jumper. Nadine, Teddy, Jason and Herman all played professional football. But athletic prowess is not the only thing they have in common; they are also refugees from the Central African Republic (CAR). After fleeing violence in the capital, Bangui, they found safety and shelter in Mole refugee camp, in the northern reaches of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

11122015 - DRC Athletes 1

Teddy Gossengha, 23, is known back home as “Gabrou,” which means ‘the mountain’ in his mother tongue, Sango. He was once the youngest player on the junior national football team, and then played for professional clubs in Bangui – first Tempête Mocaf, then ASOPT – before fleeing violence two years ago. Now, as president of the football team in Mole camp, he is intent on sharing his knowledge and skills with others. But he worries that he’s losing his desire to play. Few refugees here can play at his level, he says, and the camp’s football field is a far cry from the national stadium in Bangui, where he used to play before 20,000 spectators. ©UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 2

“Sometimes I play to remember my past. But here, we are in the bush. It is difficult to live in Mole. At first, I was even crying. There is a football field but it is not good. The environment here does not allow me to keep the level that I had. If only I could find a city or a team where I could express my talent. What strengthens a football player are the trainings. Here there are no high-level players… I would like to develop my sporting talent, because I don’t know when the war will finish. I lost almost two years. If I can, I want to recover that. The more I stay here, the more I will lose my talent.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 4

Martial Nantouna, 36, won the national championship in karate for his age group in 1998 and 2000, and was named runner-up for all of Africa in 1998. He also played football for DFC8, a team formally known as Diplomate Football Club 8eme, which was the national runner-up in 2003. He was living in Miskin, a neighbourhood in Bangui, when he heard gunshots on 15 December 2013 and fled to the airport. After three months there he crossed the river and made his way to Mole refugee camp, where he reunited with his wife and children. In Mole, he offers free karate classes three times a week, teaching students as young as six and as old as 40. He is hoping that peace will return soon, allowing him to go home and resume his athletic career. © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 5

“If someone tells me to go to the mat, I will go. I am still on the national team. My best performance was against a South African in Yaoundé for the semi-final of the Africa championship. I won 5 to 1. I lost the final because I was scared of the Cameroonian player. He was strong. He won 3-0 by knockout. I brought back two medals: the silver medal for the individual games and the bronze medal for the team.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 6

Martial excels at football as well as karate. “I never go out of Mole. I am scared. I have 75 [karate] students. I do it for free. In Bangui, the membership fee is 3,000 CFA Francs [about US $6]. Here I don’t ask for it, because we are refugees. I ask God to bring peace back to my country. My dream is to continue my sports practice. I play football too. I want to become like Didier Drogba and Samuel Eto’o. I was playing for DFC8. I was playing with Foxi Kéthévoama, who is the captain of our national team. He now plays in Hungary and was the best striker in Hungary.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 7

“I hear the announcements of the president of the karate federation on Radio Bangui. When I hear him, I don’t feel good, because before we were together. I wonder whether our karate federation in Mole could join the national karate federation in Kinshasa and join the DRC national championship. Can UNHCR help me find a football club in Kinshasa or somewhere else?” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 8

Nadine Adremane, 27, started playing football when she was 16, and was eventually selected for the women’s national team, where she played for three years. Because there’s no professional league for women in CAR, she turned to refereeing games in Bangui and was in the process of qualifying as an international referee. Nadine had been selected for the final round of tests, but was forced to flee before she got the results. She still does not know if she passed. © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 9

“I started playing football when I was 16. I was identified because of my good technique and selected for the national team. I won many games. My best memory is when I received the silver medal in the national championship. I played for the team FC105. My best game was against Berberati. I scored the goal that qualified my team for the national championship. After that I became a referee. There were four of us doing the tests [to become international referees], but I am the only one who came here. I am not in touch with the others. I will go again to the cybercafé and send them an email.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 10

Tempête Mocaf, a first-division football club in Bangui, and then for Kpèténè Star. He fled empty-handed on 5 December 2013, leaving behind all his gear and photos of his triumphs. Now he trains young refugees at Mole camp.

“I started playing football in my neighborhood when I was 10. I went to a football school as of 17. The managers of Tempête Mocaf came to the training centre and watched us play. They called me to talk to me and my trainer and asked if I wanted to join their team. I went to play competitions in São Tomé, Nigeria, Guinea and Cameroon. After that I went to play for Kpèténè Star. The team was in the second division, and I helped them join the first division.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 11

“When I fled from Bangui, I was still playing in Kpèténè Star. The team still exists, but I cannot go back. Other players are in Cameroon. When I hear on the radio that such and such teams are playing, I feel sad. Here, I train children. There are many youth here. We created the club of Mole. I do that for free because I love football. I want to improve the level of football players in Mole. I can choose the best and help them to participate into tournaments here [in DRC]. I want to become a famous trainer, like José Mourinho, who trains the team of Chelsea.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 12

Herman Ouagondas, 19, discovered football as a child, when he saw his older brother playing, and went on to join the club Video at age 15. He fled Bangui when his house was attacked and looted. Still scared by conditions back home, he does not want to return before peace has been restored. Now a refugee in Mole camp, he is intent on improving his game. Ouagondas says he wants to follow the path of George Weah, a Liberian refugee in Côte d’Ivoire who later played for major European clubs like AS Monaco, PSG in France and AC Milan in Italy. © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 13

“I started playing football when I was 10 years old. My brother enrolled me in a football school. He was playing in the club Olympic Réal de Bangui. When I was 15, I joined the club Video and then L’Avenir in Bangui’s seventh arrondissement. I went three times up to the final of the second-division championship. After that, the coach of Marché Central football club asked me to join the team. I want to become like George Weah. He learned football in his country but was forced to flee. He continued even if he was a refugee and was selected by famous teams. I want to be like the famous football players I see on TV.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 14

William Kopati, 22, was a high-jumper and long-jumper in Bangui before he was forced to flee in late March 2013, when militants attacked the house where he was living. Since 2006, he has competed several times in the national championships for high jump, long jump and 400-meter run – winning the gold medal for high-jump in 2009. This is the second time he has fled to the DRC, having been a refugee from 2001 to 2003. His dream is to continue his career in athletics, despite the challenges. © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 15

“I started athletics in 2005. Naturally, I run very well. In high school, there was a girl who was very good in athletics. She was running faster than all the boys. She asked to run against me and I ran faster than her. That’s when I started athletics. In 2009, I won the gold medal in long jump in the national championships. I cleared 1.7 meters. I entered my last competition in 2012, before I was forced to flee on 28 March 2013.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

11122015 - DRC Athletes 16

“This is my second time fleeing to the DRC. I was here in Mole from 2001 to 2003. I attended primary school here and went to high school when I returned to Bangui. My first dream is to continue with athletics. I love it so much, but I had to abandon it because of the situation in my country. My favourite athlete is Christophe Lemaitre. He runs 100 and 200 meters.” © UNHCR / Brian Sokol

Mole camp is now home to 17,000 people who fled CAR—men, women and children from all walks of life. Like them, the six figures profiled here are coping with the loss of their homes and livelihoods. But as athletes, they are also conscious that the clock is ticking—that, as the months and years roll by, they may never get the chance to resume their promising careers.

At Mole camp—more than two hours by road from the closest Congolese town, Zongo—they try to stay fit, practice their sport and train younger refugees. But they are painfully aware that they may never again have the chance to compete at the national and international level. The lucky few managed to grab a photo album or a medal as they fled. The others have only their memories.

By: Céline Schmitt