Annette Riziki is seen on campus at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. © Mike Latschislaw/University of Manitoba

Drawing on her past, a young Manitoban is changing future conversations about refugees in Canada

When Annette Riziki’s mom heard that her daughter had received a Rhodes scholarship late last year, she danced around their Winnipeg living room, telling Annette, “I told you your name would come true some day!”

The 22-year-old University of Manitoba grad explains that in Swahili “Riziki” means “blessings” and “good luck.

“[Good luck] has been coming to you ever since you were born, especially given the situation you came from,” Annette recalls her mother telling her that day, recognizing their long and difficult journey from war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to Canada.

When Annette was just a toddler the family was forced to flee the DRC during what has been called “Africa’s Great War.” Like hundreds of thousands of other Congolese refugees over the years, they arrived in neighbouring Uganda, where they lived until Annette was 14.

Life in Uganda was sometimes difficult, Annette says, but her parents tried to protect her and her siblings from the discrimination and xenophobia faced by refugees. The family felt lucky that they were able to come to Canada in May of 2011, arriving in Winnipeg to bitingly cold temperatures.

She soon learned that finding a place that felt like home could be tough. Uncertainty was a constant companion during Annette’s childhood. Being in a new country with a completely unknown culture and climate meant that her first months of high school in Winnipeg were difficult.

“I had to define my own sense of belonging”

“The biggest challenge was finding my place in school,” she says. It became a little easier when, at the beginning of Grade 11, a few students from different African countries met to form a dance group, working towards a performance at a “Culture Jam” event.

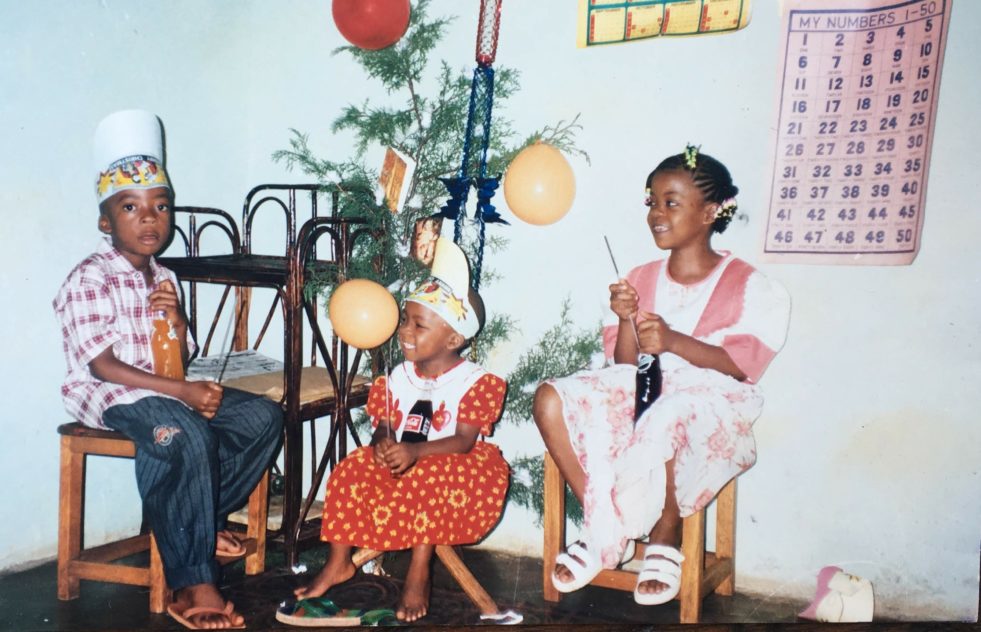

Annette Riziki and her siblings at her third-birthday celebration.

“That process taught me that I had to define my own sense of belonging,” Annette says. “And if that meant reaching out to people in my community, or people who looked like me, or people who shared my stories, then that’s what I had to do. I reached out through arts, music, dance and volunteering, and that gave me the courage to speak out about the different issues minorities and immigrants face in general.”

Pursuing a B.A. (Hons.) in psychology at the University of Manitoba, Annette found through her courses that, “not enough voices from minorities and immigrants were heard.” She noticed too that the emphasis was constantly on the trauma people endured and not the resilience they demonstrated to come through adversity.

“Being a research assistant over the past couple of years, I found that talking to people, they want the world to know ‘here’s how I made it,’ rather than what happened to them in the past,” Annette explains.

A multi-tasking volunteer for organizations such as the Immigration Partnership of Winnipeg, she says it’s her way of giving back. “I can’t be comfortable sitting down when I know that five minutes of my time could be helpful to someone. It’s also my way of trying to be a voice in a place where I think one is missing.”

Despite all her success in recent years, Annette was still surprised when she heard she had been awarded a 2019 Rhodes scholarship, the prestigious University of Oxford postgraduate prize given to only 100 students around the world. “I was just waiting for someone to call and say, ‘There was a mistake at our end!’”

Annette plans to use the award, valued at $90,000 per year, to pursue her master’s degree in refugees and forced migration studies. As for her plans after that, a clinical psychologist is one career option, working with newcomers to Canada and focusing on paths to resilience.

Regardless of her career choice, there’s no doubt it will involve changing the conversation about refugees. “It’s about giving people chances and letting them tell their own stories,” she says. “That’s what helped me in high school—being in an environment that allowed me to speak up and others to listen. When we listen we understand that people are more than their traumas.”

Written by Fiona Irvine-Goulet