Sayed Mohammad and his son stand in their damaged home in Marja.

© UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

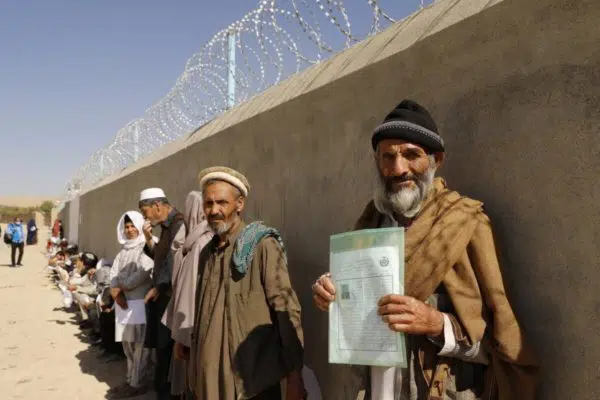

Economic collapse and drought mean that tens of thousands of displaced Afghans who have returned home are facing severe hunger this winter.

By Andrew North in Marja, Helmand

The end of the fighting in Afghanistan this summer came as a relief to farmer Sayed Mohammad*. It meant that he and his family could return to their house in Marja – a war-ravaged farming town in southern Helmand Province – after six years of moving between temporary dwellings every time the fighting got too close.

“This is the first time I’ve been home in six years,” says Mohammad, 70.

But the sight that greeted them on their return a few weeks ago was one of devastation. The entire back section of the house, which is located near a now-abandoned military base, had been reduced to a rubble-filled husk.

Much of Marja’s population was displaced over the past decade, as it became the scene of intense fighting between the Taliban and coalition and former government forces. There is hardly a building in the town that does not bear the scars of the conflict.

Together with his wife and six children, Mohammad has moved into the one room of their house that still has a roof, fixing plastic sheets over holes in the walls. “We’ve put the door back, but it’s freezing at night,” he says.

Like tens of thousands of other internally displaced people (IDPs) now back home in former battleground districts in Helmand and elsewhere in Afghanistan, he is faced with a challenge bigger even than rebuilding: keeping his family fed.

“Sometimes we get vegetables, but mostly we are living on bread and tea,” he says. “All the children are hungry.”

Adbul Wadood* 13 (right), stands in his partially damaged home in Marja. His father, Sayed Mohammad*, along with his mother and five siblings returned to rebuild after six years of displacement. © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Other people in this shattered town give similar accounts. Families cannot afford to buy enough food and those, like Mohammad, who returned in recent months will have to wait until the spring before they can start farming, and only then if the current drought eases. It is a microcosm of a nationwide crisis, with the UN World Food Programme warning that across the country only 2 per cent of the population have enough food to eat, and more than half of children under five are at risk from acute malnutrition this year.

Every week, Dr Mohammad Anwar – himself a recently-returned IDP – sees more malnourished children in the small private clinic he runs in Marja. “Babies are being brought in half the weight they should be,” he says. He estimates that at least 2,000 children across the Marja area are now severely malnourished and at risk of dying.

Food shortages are a perennial problem in impoverished rural areas of Afghanistan. Even with outside donor support, the previous government struggled to tackle the issue, but without much of the foreign aid that paid most government salaries, the banking system paralysed by financial sanctions, and a prolonged drought that has withered crops and pastures, the situation is now far worse.

Many IDPs who have returned to Marja and other war-torn districts are now deeply in debt, after borrowing money to buy food or repair their homes. Sayed Mohammad says he owes shopkeepers and other creditors at least 50,000 Afghanis (about US$500). “I need food. I need cash, but no one has given us any help so far.”

Children shelter in what remains of their family home in the Bolan area of Helmand, near Lashkar Gah city. © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

Mohammad Sadiqi, an assistant liaison officer for the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, Helmand, says the signs are pointing to “more malnutrition cases in all districts affected by heavy fighting”.

“If the situation carries on like this over the winter, most families in Helmand will become poorer than they have ever been, and many will die,” he says.

Working with local partner organizations, the UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, is responding to the needs of some 22,000 IDP families that have returned to Helmand. The focus has been on helping them to stay warm this winter as well as supporting them to repair their homes and reintegrate into communities.

A UN-wide US$4.4 billion plan for responding to humanitarian needs in Afghanistan in 2022, is due to be launched on 11 January. If funded, it will scale up delivery of food and agricultural support, health services, emergency shelter and water and sanitation.

The key factor in rising child malnutrition is insufficient food for mothers, says Dr Anwar. “They are not getting enough protein, so they can’t feed their children properly.” He adds that a lack of clean water – exacerbated by the drought – is also playing a role, leading to diarrhoea and further weight loss.

In their weakened state, malnourished children are more vulnerable to illnesses that can quickly lead to irreversible decline and death. Most children also lack the warm clothes that would provide a defence against sub-zero winter temperatures. “Some malnourished kids have been getting pneumonia,” Dr Anwar says.

He does what he can in his small clinic, but much more assistance is needed, and the root causes of the widespread hunger remain.

The arid landscape of Helmand where the effects of a severe drought are apparent everywhere. © UNHCR/Andrew McConnell

The effects of a crippling drought are apparent everywhere. Irrigation canals have dried up and crusts of salt cover many fields. The use of solar-powered pumps to tap ground water in order to grow opium – the raw material for heroin – has pushed the water table lower, drying up the soil and leaving salt deposits behind that make it even harder to grow legal crops.

“All of our youth are leaving.”

The start of the year finally brought rain, but in such large quantities that it caused flash flooding in both Helmand and neighbouring Kandahar, washing away homes and fields. Much of the water was lost rather than being stored and so any mitigating effect on the drought situation is likely to be temporary.

Subscribe to UNHCR’s mailing list

“If the water stops for good, we’ll have to go to Iran or Pakistan,” says Fazl Mohammad, another former IDP, who returned to Marja in November. “Or we will just dig graves for ourselves.”

Many are already on the move – no longer fleeing war, but the combined effects of climate change and economic collapse. “All of our youth are leaving,” says UNHCR’s Sadiqi. “What else can they do?”

* Names have been changed for protection purposes.

Originally published by UNHCR on 10 January 2022.