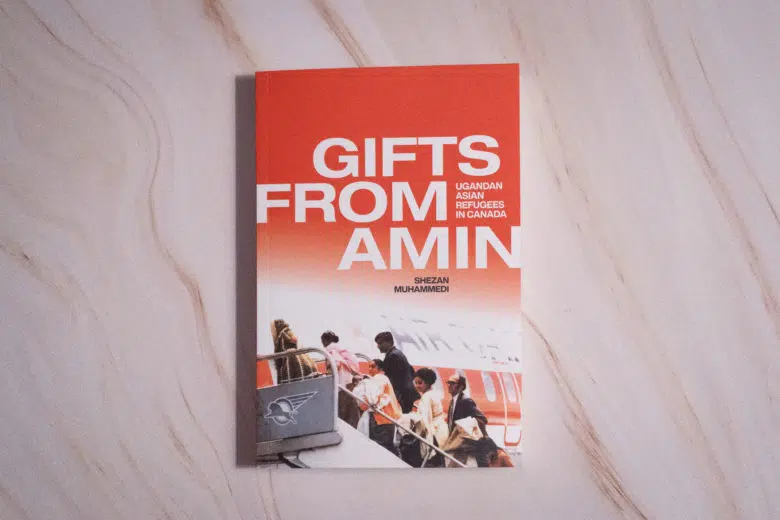

‘Gifts from Amin’ that keep on giving: Q&A with author Shezan Muhammedi

On the 50th anniversary of the first charter flight bringing 148 Ugandan Asian refugees to Canada, Shezan Muhammedi publishes a stunning testimony of the South Asian expulsion in Uganda

By Soo-Jung Kim

Photo: © UNHCR / Soo-Jung Kim

In Gifts from Amin: Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada, Shezan Muhammedi recounts the experiences of the nearly 8,000 Ugandan Asians resettled to Canada. He follows their journey from the dangers and uncertainty after Idi Amin’s expulsion decree on August 4th, 1972, to rebuilding their lives in Canada.

The following is an excerpt of his conversation with UNHCR’s Soo-Jung Kim which has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: Shezan, tell me about yourself. Who are you? What do you do?

A: I’m Shezan Muhammedi. I’m the youngest of three boys. My mom and her family came to Canada as refugees from Uganda in the 1970s. They flew into the military base in Montreal and then ended up settling in Ottawa. My mom has been here for exactly 50 years — and we’ve been living in Ottawa ever since. [My brothers and I] all went our different ways.

I went to Queen’s University for my undergrad and then did my Master’s and PhD at Western University. After I graduated, I ended up working for an international nonprofit called Focus Humanitarian Assistance, which is part of the Aga Khan Development Network. They specialize in responding to human disasters — and natural disasters as well. I was supporting the resettlement of refugees largely from Afghanistan and Syria in Europe. I now work at Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC).

Q: Your interest in migration and displacement — was something you always had or was it prompted during your studies?

A: It came late. I had started my undergraduate in history with the idea of becoming a high school history teacher. That was the end goal for me. And in my third year, I got really interested in identity studies.

A lot of the time, especially as a person of colour, we’re told our physical appearance is who we are and not necessarily our history. But that was one of the biggest takeaways, that our history informs our sense of self, not our biology. And it was something I really wanted to dive into.

And I was super curious because as the child of a newcomer, we have these multiple identities, right? We’ve got our parents who are clearly newcomers themselves and they have that immigrant identity. But we grew up here in Canada, for example. What does this mean and how do we clash with our parents in many different ways, only because we’ve grown up in such different contexts?

Then it wasn’t really until I started my Master’s that I really got involved with this Ugandan movement. I was always fascinated with my mom’s story. She had this incredible story of resilience. She came at such a young age, she was 19. She looked after her two younger brothers and my grandma, put everyone through school, worked for over 30 years at the bank, and is really selfless with a lot of gratitude for being here and has a huge, open heart.

I was curious about how her experience played out over the years and what was the real thing that happened. Not just what she had told me. How did everyone else cope with this experience? Especially coming to Canada in the 1970s and going to cities in Canada that I’ve never even heard of.

© UNHCR / Soo-Jung Kim

Q: Can you give us a brief taste of what your book is about?

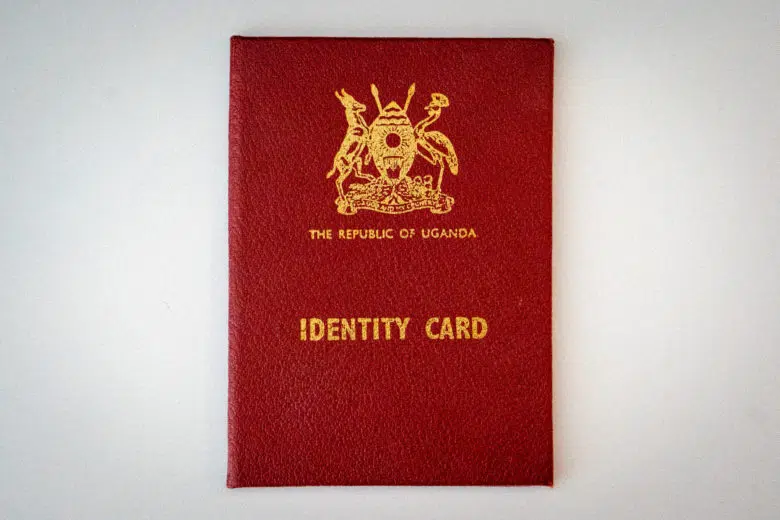

The book overall follows the trajectories. We start with the history of Uganda and a lot of that initial movement from the Indian subcontinent. And a lot of that had to do with colonial expansion. It really talks about that movement itself; how many generations had been there and then their establishment.

And then the book focuses on the expulsion decree itself. So, what was the context? Why did Idi Amin decide to make this decision? What were the local dynamics and what was the international response? And why did Canada get involved? It was quite interesting because we didn’t have a formal refugee policy in Canada until 1976.

And then the last chapter talks a lot about identity.

Listen to the full summary. ⤵️

I think the other thing was almost everyone described instances of discrimination. And it was challenging. It was really challenging for folks to talk about it because they had to fight this concept of being an ungrateful refugee.

Q: ‘Ungrateful refugees’ that’s an interesting term. How did this kind of sentiment impact your interviews?

A: I was doing these interviews between 2014 and 2016, so I think if I did these interviews now, we would definitely see a very, very different response. I think people would be a lot more open to talking about some of the challenges they faced because we’ve had major events around the world with race relations.

I also think there’d be very different rhetoric in terms of refugee resettlement. So now that we’ve had the Syrian crisis, which when I was doing these interviews, really hadn’t hit home for Canada just yet, and now more recently with Afghanistan and Ukraine, I think people have new reflections on what it means to be a refugee and what that identity is all about.

I think that was really tough. Everyone did talk about discrimination and what it meant to them. For some folks, it was employment discrimination. That was the most common thing I heard and remains a major challenge even today. One of the biggest barriers to integration anywhere is, “No one recognized my credentials, and I didn’t have, ‘Canadian experience.’” And then a lot of it was just straight harassment. They often would talk about it later on in the interviews once they felt more comfortable, of course.

That was the other thing about the interviews themselves. I had geared them to be completely open-ended. While I had a list of questions prepared, I basically started with, “Tell me about your family’s upbringing in Uganda.”

“I really didn’t want to force them to recapture what was important based on my view. I wanted to give that agency back to folks… the opportunity to tell history the way they see it.”

And then I just followed them wherever they went. I really didn’t want to force them to recapture what was important based on my view. I wanted to give that agency back to folks because that’s the biggest thing we see all the time, is this lack of agency for refugees, the opportunity to tell history the way they see it, and that’s important to them.

Q: Your book title, Gifts from Amin — how did you come up with that? My theory is that despite all challenges and obstacles they’ve encountered, there were many positive outcomes from the hardships they’ve endured.

A: In hindsight, after we had come out with the title and people have been reflecting on it, it’s really meaningful, right? It’s this juxtaposition because they were thrown out of the country and what does it mean?

There’s this really famous joke that the Aga Khan and many others always tell — that there’s a Ugandan Asian that made it to Canada. And he has this huge photo of Idi Amin in his living room. And his friends always ask him, “Why on earth do you have this?” He says, “Well, every day we thank him for throwing us out and bringing us here to Canada.”

The inspiration for the title comes from Adrienne Clarkson’s book. She wrote a book called Room for All of Us, and she talks about one Ugandan Asian refugee family that comes to Canada. And at the end, she says, “This community was a present from Idi Amin to Canada.” So, I wanted to play on that to say, ‘Gifts from Amin.’

© UNHCR / Soo-Jung Kim

Q: What would you say was the most surprising? Was there anything shocking you heard during the interviews?

A: There was a lot, I think. Every interview had something truly unique that spoke to me differently. For some folks, there were some common themes. The sense of humility and gratitude amongst this community was profound. That sense of gratitude and that they’re just so thankful to be in Canada and to have these opportunities and to raise their families here.

I also did not expect how candid people would be. I thought they would have their guard up a little bit. People were incredibly self-reflective to say things like, “That was a regret. If I’d gone back, I would have gone about it differently.”

Or they alluded to different things. One of the people I interviewed did a really good job of saying, “Of course, we discriminated against [local Africans]. Who were our house staff? Who were the people that worked for us?” And he says, “It’s funny because now that we’re in Canada, you know, 20, 30 years later, we’re all denying we did this, but we all did.” So, it’s fascinating to see that colonial legacy, the impact, and how people are reframing this today.

That same person I interviewed also talked about how when he first came to Canada and got his first job, he worked a 12-hour shift but got paid for eight. And he said, “How interesting is it, that this is exactly what we used to do to the people that used to work for us.” And he’s said to feel that same exploitation is really difficult and a wake-up call.

Q: If there was one key takeaway you want the readers to take from your book, what would that be?

A: The key takeaway is there’s no difference between us and refugees. We have struggles and challenges, and face adversity in so many ways. But we also have the same hopes, dreams, and aspirations.

When I hear someone talk about a newcomer, when I’m watching the news and they’re talking about a migrant caravan or things like that, [that people should be thinking this] could be my neighbour. This could be one of my closest friends.

That always hit home for me when people would say things like, “Go back to your own country. Why are you here?” Or, “Refugees and immigrants are just coming to this country to take jobs away from us and bring their values that aren’t accustomed to the Canadian way of life.”

I would take it personally because you are talking about me. You’re talking about my mom. And I think that’s what I really want people to understand. At this point in our Canadian history, we are a country of newcomers. Other than those that have been here from time immemorial, our First Nations communities, all the rest of us are guests on this land. And I think that’s the key for us to all remember we’re frankly all in this together.

Q: So, I have to ask, did you dedicate your book to anyone in particular?

A: It’s dedicated to all Ugandan Asian refugees. They’re the number one feature because they obviously made this book happen. The reality is that frankly I did nothing. I captured these stories and I put them together. This book is only so meaningful and carries a message to the Canadian public and the world more broadly because they’re human stories of resilience.

Q: Are there any last reflections you have more broadly on refugee crises happening worldwide?

It’s sad, if I’m being honest, from my own perspective to see what’s happening because the scope of the problem is huge. And it’s only going to get bigger, especially as we start to see the effects of climate collapse.

When I reflect on global resettlement, [it’s challenging because these are the one per cent of people that have UNHCR refugee status that are resettled]. It’s a tiny number of folks. I think that was one of the really interesting things that came out as feedback from my manuscript, is, you have to talk about resettlement bias.

[My book talks] about a very small number of people that actually found a place to go. And this is not the common experience. Many will have to stay in protracted refugee situations for a very long time or may never be relocated. We have these situations around the world where people are born in refugee camps that have lived there for 20, 30, 40 years.

As much as I want to say that Canada benefited from this experience, at the same token, my mom was one of the very lucky few when we look at the grand scheme of resettlement around the world. This is a very select group of people that made it — and not everyone is as lucky or fortunate.

Dr. Shezan Muhammedi is a senior policy analyst with the government of Canada and an adjunct research professor in the Department of History at Carleton University. From 2017-2022, Shezan worked for Focus Humanitarian Assistance, leading a resettlement program for newly arrived asylum seekers and refugees in Europe. His experiences as the child of a Ugandan Asian refugee have fueled his passion to help displaced peoples and vulnerable communities.

You can purchase his book, Gifts from Amin: Ugandan Asian Refugees in Canada here or watch the full broadcast of his book launch here.